In November 2025, I was awarded a 5-year SNSF Starting Grant to lead a large project on understanding Neptune-like planets. Here is a brief summary of that project and what will be involved.

Thanks to surveys like Kepler, we now know that most stars like the Sun host a place between the size of Earth and Neptune, and most of those planets orbit close to their stars – usually with orbital distances closer even than Mercury. Without such a planet in our own solar system it is hard to understand what such planets are made of and how they might form.

But we now have a remarkably detailed & growing cache of observations for such planets. This has been helped by multiple developments in the last decade. On the ground, our high-resolution spectrographs have become even more powerful (e.g. ESPRESSO, Maroon-X, etc), enabling precise masses for planets down to a few times the mass of Earth. In space, NASA’s TESS spacecraft has rapidly found thousands of planet candidates, especially Neptune-like planets orbiting nearby & bright stars, and ESA’s CHEOPS satellite has been instrumental in following-up many of these (see e.g. my last two research posts on here). And last but not least, NASA’s JWST has for the first time revealed the contents of the atmospheres of a large number of small Neptune-like planets.

We now have dozens of Neptunes & sub-Neptunes with precise masses, radii and atmospheric measurements. This has resulted in the first estimates of bulk compositions for some of these low-density planets, revealing some exo-Neptunes which are rich in water, others that seem depleted in water, and yet more where their atmospheres appear too thick for precise measurements.

Despite these measurements, there exists much uncertainty in exactly where these planets formed and what they are made of. Some theories suggest they form in the outer ice-rich regions of their solar systems and then migrate into their current locations, while others suggest they grow close-in from principally rocky material. And the current set of observations are extremely patchy with biases toward the observation of certain planets (such as close-in planets around M-dwarfs).

As I see it, there are multiple issues with the current observations of exo-Neptunes:

- Planets at longer orbital periods are missing because they have not been found via consecutive transits in TESS, and their confirmation takes time

- A fraction of detected planets have not yet been sufficiently characterised (in e.g. mass using RVs or atmospheres using JWST), leading to incomplete and biased target lists

- Radii, masses & atmospheric information is derived on a per-target basis with different extraction and retrieval routines, leading to results which cannot be directly compared

- There has been no study of planetary demographics to measure the underlying occurrence rate of compositions derived via atmospheres

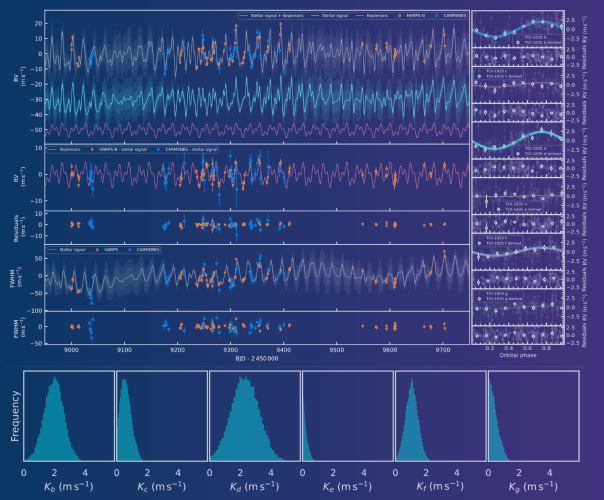

The project is therefore designed to fill these knowledge gaps. Starting from a golden sample of around 10,000 stars for which sub-Neptunes can be detected & characterised in both radial velocities (RVs) and JWST, the plan is to uniformly detect and characterise all Neptune-like planets orbiting these stars. The first key step is to use advanced techniques (e.g. machine learning) to detect missing exoplanets around these stars in TESS photometry as well as to assess how likely planets of given period & radius will have been detected. These planets will then be confirmed via CHEOPS observations if necessary. The next step is to both measure these planets masses as well as to search for additional planets in the system using RV observations (and, in some cases, transit timing variations – TTVs). This will produce densities for the exo-Neptunes as well as reveal the system architecture – e.g. whether the planet is alone or in a multiple system. The next step is to take transmission spectra of the ~100 planets within this sample to uniformly derive atmospheric abundances for the sample. This will be a mix of existing (e.g. archival) observations as well as new observations performed to make sure all planets have similar datasets.

The final goal is to take all of these observations and analyse them together in order to produce maps of exoplanetary compositions as a function of planetary age, architecture, etc. This can then be compared with theoretical predictions in order to help answer key open questions in planetary formation and evolution.

To apply for a PhD in the group focused on the detection of new exo-Neptunes (see below), head to the University of Bern job portal (deadline: 30th Nov 2025). In late 2026 (deadlines early summer 2026) I will also hire an additional PostDoc working principally on measuring precise masses and system architectures (using RVs & TTVs), as well as a PhD focused on atmospheric observations of exo-Neptunes.

Phase I – detection

Detecting sub-Neptune exoplanets forms the first part of the project and the thesis of topic of the first PhD student (to start in early 2026, ideally before April). The goal is to reliably recover all of the transiting Neptune-like planets in TESS data for golden sample of ~10,000 nearby & bright stars. These will form the starting point for the characterisation of these planets in masses & atmospheres. The vast majority of transiting planets have already been detected by one techniques or another, and many already have RVs or even spectroscopy. But some are missing – typically those on longer orbits with only a handful of transits, or orbiting bright or active stars where traditional detrending techniques fail. In order to reliably detect these we need a different approach which better able to find transit-like features in noisy TESS lightcurves. As these candidates may not have clear orbital periods if the transits are non-consecutive, one next step will be to help pin down the true periods via CHEOPS observations. Additionally, we want to be able to assess how common a particular planet type is, which requires an answer to the question “around which stars could this type of planet have been detected?”. So a secondary part of Phase I will be to reassess the occurrence rates of Neptune and sub-Neptune planets. This is key to finally being able to assess the occurrences of exo-Neptunes as a function of planetary compositions and formation pathways.

However, all is not lost. TESS searches an area around 5.5% of the sky in one pointing (20x more than Kepler) and will eventually cover 60% after its 2 year mission (100x more than Kepler!). That wide field also means that TESS can focus on closer and brighter stars. In fact the average TESS planet host will be about 3 magnitudes brighter than a Kepler planet. Some of them will

However, all is not lost. TESS searches an area around 5.5% of the sky in one pointing (20x more than Kepler) and will eventually cover 60% after its 2 year mission (100x more than Kepler!). That wide field also means that TESS can focus on closer and brighter stars. In fact the average TESS planet host will be about 3 magnitudes brighter than a Kepler planet. Some of them will